| Appendix D – Singapore Country Summary |

The Government Context

Organisation of Government (see note i)

Singapore is a parliamentary republic; a city state with a governing structure patterned on the British system of parliamentary Government. Executive power lies with the Prime Minister and his Cabinet who direct and control the Government and is responsible to Parliament. Each of the Government ministries is headed by a Minister who is a Member of Parliament, and a Member of the Cabinet and is accountable to the Parliament for all the Ministry's affairs.

Singapore has only one level of government i.e. national and local government is one and the same - a form of government that reflects the country's small population of about 4.01 million. As at January 2002, there were 14 ministries, 21 Government Departments and 68 statutory boards.

As a governing body for both the nation and the city, the Singapore Government is responsible for planning, budgeting for and supervising the majority of key services. The actual delivery of some services has been devolved to statutory boards. These are an autonomous Government agencies set up by special legislation to perform specific functions. Some statutory boards have formed subsidiary companies to add further flexibility to their operations for example, charging fees for service provided. Others have been further corporatised and subsequently privatised. These include power and gas provision, telecommunications, and broadcasting.

The Civil Service (see note ii)

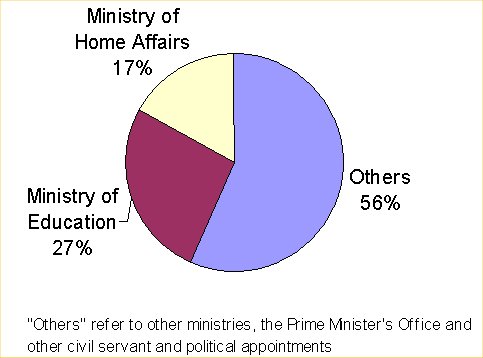

There are a little over 114,500 people working in the Singapore public sector, including members of the civil list, political appointments and civil servants who work in 14 ministries and employees of the statutory boards. The public sector accounts for around 5.23% of the total working population.

What is normally called the ‘Singapore Civil Service’ excludes the statutory boards, government-owned enterprises and the Singapore Armed Forces. The Civil Service proper employs close to 63,300 staff, or 55% of the overall public sector. Within the Civil Service, some 270 (0.43%) belong to the elite Administrative Service and hold key leadership positions in government ministries and the major statutory boards. Some are also seconded to Government linked companies.

The equivalent of the Hong Kong Disciplined Services (or what are called the Home Affairs Uniformed Services in Singapore) are considered as part of the Singapore Civil Service, and come under the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA). The exception is the Customs and Excise Department which sits under the Ministry of Finance. The number of employees in the Hong Kong Disciplined Services equivalents is around 20,000, of whom the police account for about 13,000 or 65% (this figure excludes National Servicemen).

The overwhelming majority of staff in the Singapore Civil Service are employed on a permanent basis. Fixed period contracts are not widely used - only for projects requiring very specific skills. Continuity of service or skills availability is a key consideration for converting contract staff to continuous terms of service

The key values underpinning the Civil Service are:

Principles |

Practices |

Leadership is key |

· Strong political will and example of political leaders and public servants in terms of integrity and honesty (through strict adherence to a code of conduct) · Constant re-inventing of the way the Government does its business in response to external challenges |

Reward for work, work for reward |

· Meritocracy and equal opportunities for all in terms of - open and fair recruitment and selection based on educational qualifications and relevant experience - effective performance appraisal · Market rates for civil servants |

Pragmatism and a sense of urgency |

· Continual learning by doing and through constant review and improvement · Will to make and implement difficult decisions |

The Singapore Civil Service is generally regarded as efficient, thorough, strategic and pragmatic having facilitated demonstrated improvements in service delivery over recent years. The current upgrading and increasing emphasis on IT, however, is of concern to some sectors of society, especially citizens of an older age profile, arguing that these developments seem to be serving the Government more than the public. As an employer, the Civil Service is viewed positively, in particular as a training ground for new recruits.

Public Sector Reform

Public sector reforms (see note iii)

The Civil Service has undergone some significant reforms over the past two decades beginning in the early 1980s. The focus has been improved delivery of service to the public and a more devolved financial management, as set out below:

· Managerialism and budget reform. Principles of business management were introduced into the Civil Service. Key initiatives included the introduction of block vote budget allocation system and a management accounting system (activity based costing) and implementation of zero-based reviews within the ministries

· Corporatisation/ privatisation and establishment of statutory boards. Privatisation is one of several long-term means considered by Government to achieve progressive decentralisation and devolution of many traditional roles and functions. A degree of Government control is still maintained through share ownership in the numerous state and quasi-state companies, organised under wholly owned government holding companies (e.g. the Temasek Holdings Private Limited), and also through movements of former civil servants to head key positions in such organisations. A mixture of privatisation, corporatisation, formation of statutory boards and other managerial initiatives has been used as tools to enhance and maintain efficiency of Government organisations.

· Shift to client-oriented public administration. The shift towards more client-centred public administration has taken the form of providing more efficient customer-based services, through streamlining rules, procedures and red-tape using computerisation and other approaches. The most recent initiative is the introduction of PS21, or Public Service for the 21st century, which aims to transform mindsets and create a culture within the Civil Service that welcomes continuous change for greater efficiency and effectiveness.

These initiatives, coupled with a Government directive in 1986 to reduce its workforce by 10% over the subsequent five years, were successful in improving overall efficiency. There were no recruitment freezes but hiring policies were limited to replacements for necessary personnel. Attempts to improve customer service have also been successful - particularly counter and processing services in Government Departments and offices. A holistic approach was adopted in implementing such initiatives, and accompanying changes were made to the appraisal system, rewards and development systems to support the strategic imperatives.

Pay specific reform (see note iv)

Pay reform in the Singapore Civil Service has taken place in the broader context of personnel-related reform. In particular, this included constitutional amendments in 1995 to delegate recruitment and promotion functions, for all grades of staff except the Administrative Service, from the Public Service Commission to the various ministries, through a system of Personnel Boards.

Key developments that have characterised the pay reform include:

· Introduction of a flexible wage system in July 1988 driven by the economic recession of 1985. This enabled the award of wage increases, on top of salary increments, as a mid-year or year-end variable bonus. It also provided the government with increased flexibility to adjust wages in response to future economic situations

· Move towards more competitive salaries for top civil servant talent. There was a substantial salary increase for both Administrative Service officers (about 20%) and other senior civil servants (from between 21% to 34%) at the end of 1993 in response to low recruitment and high resignation rates. In 1994, salaries for senior staff were pegged to those in the private sector by setting formal benchmarks. Two points are used: Superscale G for senior civil servants and Staff Grade I for Ministers. Other salaries are then interpolated or extrapolated from these two points.

· Introduction of performance related pay for all civil servants, linked toindividual performance

· Encashment of medical benefits and the gradual phasing out of pensions as part of the government's move to reduce liabilities for the future generations. The former resulted in an addition component to civil servants’ salaries of 1% to be used to contribute to their individual Medisave account. This is a national savings scheme that helps individuals set aside part of their income to meet hospitalisation expenses.

· Introduction of salary ranges for senior civil servants to increase flexibility in personnel management. Officers can be rewarded with merit increments within their salary range each year depending on their assessed potential and demonstrated performance.

Broad impact of reforms

On the whole, these reform initiatives have been seen as successful in meeting their stated objectives. It is still too early to tell, however, whether more recent interventions, such as the introduction of salary ranges for senior civil servants and the performance bonus, have had an equally positive impact. Overall, the Civil Service has found that effective change management and a flexible implementation approach have been critical to ensuring successful buy-in of these change initiatives.

Overview of Current Pay and Administration Arrangements (see note v)

Pay administration principles and policies

Determination and implementation of pay policy

Pay policies are centrally determined by the Public Service Division (PSD), who also ensure that various ministries implement them in a consistent way. With the devolution of personnel functions to the various ministries there is now greater flexibility for them to influence pay policies and practices relevant for their staff. A recent example is the Ministry of Home Affairs' review of the Home Affairs Uniformed Services in 2000 where an external consultant was engaged to undertake the review of these services.

The Ministry of Finance is in charge of the overall budget for each ministry, which would include the budget component for manpower expenditure. PSD would oversee the budget pool for specific salary components such as Performance Bonus. Ministries are responsible for the administration of their staffs’ salaries, within the frameworks that are jointly established with PSD. Ministries have autonomy to make certain variations to cater for the specific needs of the relevant services within the overall Civil Service guidelines as long as they do not exceed the block vote budget allocated to them.

Pay principles

The Civil Service operates on the following pay principles:

· Comparability with the private sector. In recent years, there has been an increased emphasis on competitiveness of civil servants' pay vis a vis the private sector, although the policy is for their pay to be pegged to, but not to lead the market

· Annual salary reviews. To remain competitive, Annual Salary Reviews are conducted to identify salaries that need revision. The Civil Service takes into account the annual wage adjustment recommendations of the National Wage Council and follows its principles of wage adjustment in salary revision exercises

· Flexibility in the wage structure of civil servants. The wage structure for civil servants is made up of a number of components which can be adjusted based on the performance of the economy without affecting take home pay too adversely. Recently additional flexibility has been added through introduction of by performance bonus linked to individual performance.

· "Clean wage" policy. Civil servants are paid "all cash" wages which is indicative of a move away from paying a wide variety of allowances, provision of free housing, and offering free medical benefits. One initiative was a transfer from the Civil Service pension scheme to a national Central Provident Fund (CPF) scheme.

· Internal Relativity. Educational qualifications remain an important factor in determining starting salaries and for entry into the Civil Service

· Long term strategic view. The Civil Service adopts a long term strategic view on pay administration matters. This has had some important implications for the design of the pay structure and system:

- The Civil Service has sought to strengthen the links between pay for the high level Administrative Service and top private sector salaries. This reflects a recognition of the need to stem the outflow of good officers from the Civil Service which would ultimately affect succession to top positions

- While there is a desire to adopt the latest and best practices, policy makers are always cognizant of the need for long term public accountability

- PSD's preferred stance on Civil Service salaries is for adjustments to fluctuate within a narrower band than is the case for the private sector. This allows for greater stability in the longer term, which is seen as important to ensure that employees remain motivated to deliver quality service.

Pay structure and components

Grading structure

Jobs in the Singapore Civil Service are classified according to four Divisions (I to IV) based on very broad levels of work and educational qualifications, as set out below:

Division |

Details |

Division I |

Generalist administrative and professional grades (requires a university degree) |

Division II |

Includes the executive and supervisory grades and requires at least an Advanced General Level Certificate of Education |

Division III |

Includes the clerical, technical and other support grades with an educational pre-requisite of a General Certificate of Education |

Division IV |

Workers engaged in manual or low-level routine work (e.g. office attendants) are placed in this category |

These are further disaggregated into broad occupational groups e.g. administrative group, nursing group etc. Each group is divided into a single recruitment grade (the term grade in Singapore is synonymous with the term ‘rank’ in Hong Kong) and one or more promotional grades, reflecting different levels of work responsibility and difficulty.

The grades of the administrative group (Senior Officers and the elite Administrative Service) are all in Division I but those of other groups can span Divisions for example, a student nurse will be in Division III, and a chief nursing officer in Division I.

The terms and conditions of many groups are formalised in schemes of service, which prescribes the entry qualifications, grades, salaries, broad duties and responsibilities, probationary period, appointment, career structure and promotion requirements of its group. One of the key developments over the last five years was the amalgamation of schemes of service in the Civil Service into broad Service Groups: Senior Officers, Management Support Officers, Technical Support Officers, and Corporate Support Officers. This change was aimed at widening the development prospects and improving the deployability of officers.

Approach taken in designing pay structures

Pay structures are designed using a hybrid of the job-based approach. Job evaluation is used to rank jobs within a certain scheme of service into ascending levels of difficulty and responsibility. The aim is to ensure:

· Equal pay for equal jobs

· Promotion always involves movement to positions of higher job responsibility.

The internal relativity of the various schemes of service and their salary ranges, however, are not an issue in practice as they are all pegged to their respective market rates according to qualifications and, in most cases, age.

Civil Service pay structure

Since 1988, the Civil Service has moved towards a flexible wage system. The current pay structure has flexible components both in the monthly wage and annual bonuses:

Monthly Wage Components |

||

|

Basic pay |

Fixed and counted for the purpose of computing an officer's pension. |

|

|

Non-Pensionable component (NPC) |

Found in the salaries of officers who are on medical benefits schemes with co-payment features. NPC helps offset the co-payment expenses officers have to make for their own healthcare. Officers who did not opt to convert to medical schemes with co-payment features do not receive this component. Not counted for the purpose of pension computation. |

|

|

Monthly variable component (MVC) |

Comprises the 1982-84 National Wages Council (NWC) Wage Adjustments. MVC is counted for the purpose of computation for pensionable officers and can be adjusted in times of poor economic performance. |

|

|

Non-Pensionable Variable Payment (NPVP) |

Comprises all NWC wage adjustments and salary revisions made from 1993 onwards. It is not counted for the purpose of pension computations and can be adjusted in times of poor economic performance. |

Annual Bonuses |

||

|

Non-Pensionable Annual Allowance (NPAA) |

1 month's pay - similar to the Annual Wage Supplement or 13th month pay in the private sector. It has been paid since 1972. It is paid in December every year and can be removed in times of poor economic performance. |

|

|

Annual Variable Component (AVC) |

Up to 2 month's pay - this component was built up from the NWC wage adjustments for the period 1988-1991 when the NWC wage adjustments that were payable to civil servants were used to build up the AVC rather than incorporated in the monthly salaries. The AVC is paid in 2 instalments -in July and December and can be removed in times of poor economic performance. |

|

|

Special Bonus (SB) |

This component is a one-off payment that is made during years of exceptionally good economic performance. |

|

|

Performance Bonus (PB) |

This component is variable and depends on the performance grading of the individual officer. The Scheme covers officers at the senior and middle management levels. |

The pay structure for most of the Civil Service is characterised by fixed salary scales with fixed minimum, maximum and increments. The exception is the Administrative Service' salary scale and salary points which have been replaced by a system of salary ranges in 2000.

Under the current arrangements, the variable and semi-variable components can amount to 30% to 40% of the base salary to provide an adequate cushion for adjusting salaries during times of economic recession. Employees are constantly reminded that a significant part of their earnings are “at risk” and dependent on the health of the economy as a whole.

There are few allowances given under the Singapore Civil Service pay structure. The more common allowances include:

· A transport allowance for senior civil servants. This is in line with the "clean wage" policy and is also consistent with the Government's wider policy to control the number of cars in Singapore

· A special allowance for Administrative Officers, Statutory and Political Appointments. An allowance equivalent to one month’s salary in recognition of officers who hold premier positions, or who have been assessed to have the potential to hold senior positions

· Special allowances are paid to more junior staff where specific risk or hazardous working conditions apply eg certain areas of police work.

Typical benefits include vacation and medical leave, low interest rates for housing, housing renovation, vehicle and computer purchases, use of local Government Holiday Bungalows and membership at the Civil Service Club. There may be some minor variations across the ministries e.g. some ministries allow the use of overseas holiday bungalows and chalets.

Pay system

As mentioned above, decisions on salary upon appointment and promotion are made by the various Personnel Boards according to PSD guidelines. With the exception of senior civil servants, pay administration is the responsibility of the respective ministries.

Key features of pay administration process

The key features of the pay system for the Singapore Civil Service are as follows:

· Determination of entry pay. Entry salary is determined based on qualifications, relevant years of experience and national service. Honours degree holders are paid higher salaries than pass degree holders. Applicants who have completed National Service are awarded an additional increment in recognition of the service they have performed.

· Movements within salary time-scale or salary range. Officers on salary time-scales progress on the basis of fixed annual increments until they reach the scale maximum. Only in rare exceptional cases do increments vary from the norm. Annual increments have traditionally been granted in Singapore virtually automatically, except for flagrant displays of inefficiency (or disciplinary cases such as officers who have been charged for corruption).

Officers on salary range are given merit increments within their salary range each year depending on their assessed potential and demonstrated performance.

Systems and mechanisms for determining pay levels and pay adjustments (see note vi)

The systems and mechanisms for determining pay levels and pay adjustments are partially decentralised. The pay structure is centrally managed and regulated by the PSD, which carries out an annual state of service review to examine the various services' ‘health’ in terms of attrition and vacancy rates, pay competitiveness etc. In addition, various ministries are given the autonomy to review the competitiveness of their unique schemes of service. Comparators used include the wider public service and the private sector. Such data can be used to inform the ministries' consultations with PSD. The basis for pay level adjustments in the Singapore Civil Service is broad comparability with the market but not to lead it. At the same time taking into consideration any prevailing recruitment and retention issues.

Actual pay levels and pay adjustment mechanisms

For senior civil servants a formula has been set to peg pay to salaries of top earners from a basket of 6 professions. These have been chosen based on similarity with the nature of work performed by such civil servants e.g. bankers, accountants, engineers, lawyers, multi-national companies and local manufacturers. The point of comparison is the average of the principal earned income of the 15th highest tax payer, aged 32 years old, belonging to each of the 6 professions.

It is clearly stated that the benchmark figure is an estimated average, not a fixed entitlement and includes basic pay, NPAA, AVC, a typical Performance Bonus, a car allowance (plus imputed tax), plus a new Special Allowance. Benchmarks are computed annually, based on income tax returns data. Salaries automatically follow the benchmarks up or down, albeit after a lag. The benchmarks are reviewed every 5 years.

For most civil servants (ministers are an exception) the benchmark is not “discounted”. This is based on the argument was that it would be unrealistic and unfair to expect civil servants to make a financial sacrifice compared to their private sector peers, in order to enter public service.

The first review of the Administrative Service benchmark in 2000 revealed that salaries in the private sector were anything up to 50% higher. Instead of accepting these figures at face value, and increasing salaries to match them, the Government thoroughly reviewed the salary benchmark methodology and framework. It was found that overall the benchmark was sound in that it had been effective in attracting and retaining good officers in the Administrative Service for the past 5 years. They chose, therefore to retain the benchmark approach as it stood.

For the rest of the Civil Service, PSD undertakes comparisons with the market pay on an annual basis. The comparison is against aggregated income data from the CPF Board and the IRAS. Ministries are given the autonomy to engage consultants to conduct salary surveys and the outcomes will be used to inform their consultation with the PSD regarding the status of specific schemes of service. Services suffering from critical staffing level will be given interim market adjustments when the gap with the benchmark widens beyond a certain amount, for example 15%.

Recent salary adjustments (see note vii)

A range of factors has triggered salary adjustments and often a fine line has to be trod between balancing economic conditions with recruitment and/or retention issues.

Government considers that in times of economic downturn, it has a duty to send a clear signal of the gravity of the situation, and to set an example by taking the lead in wage restraint. As such as recently as last year, political appointment holders and senior civil servants, whose salaries are tied to the private sector salary benchmarks, had their monthly salaries cut by 10% from 1 Nov 2001 for 12 months. No year-end AVC payments were made except to lower level civil servants (Division II-IV) whose salaries are lower. All other adjustments to their salaries would be frozen during this period. The cuts affected the variable components of the monthly salary but not the basic pay.

The Singapore Government had to took a firm stance on this issue, and worked together with the Unions to implement what was a hard decision. The flexible elements of the salary structure enabled the ability of the Civil Service to respond and adapt to meet market conditions.

The existing systems and mechanisms for determining pay levels and adjustments allow for regular tracking of market pay movements. Pay trends also take into consideration all working employees so there are no issues related to statistical selection. The potential downside, however, is that there may be over-benchmarking as the earnings data may vary due to market seasonal and windfall factors. Although salaries are benchmarked against the market, promotion and movement up the grades are still perceived to be generally slower than in the private sector except for the Administrative Service.

Whilst it is the view of certain sectors of the population that top level benchmarking are somewhat generous , on balance the current arrangement are deemed to have worked for Singapore . Potential areas for improvement may include the appointment of an independent or even an international panel to review its key benchmarking approach and to study why the Civil Service are not attracting and retaining enough top talents. For the other staff, job-based surveys could be used as a starting point for better job comparability instead of using only aggregated data from the Central Provident Fund and the income tax department.

Arrangements for the Disciplined Services

The Singapore Police Force is part of the Ministry of Home Affairs, which is responsible for internal security and law and order.

Pay principles

The general principles of pay as set out above apply to these grades of staff although there are some variations and allowance to cater for the specific needs of certain groups of staff. For example, recruits may join as a Senior Officer, a Junior Officer or as a Home Affairs Senior Executive (equivalent of Senior Officers in other Government bodies). Entry salaries depend on educational qualifications, national service and in the case of operational command positions, requirements for certain physical qualities. Entry salaries for this grade of staff are approximately 10% higher than those paid by the private sector.

Comprehensive review of the Home Affairs Uniformed Service in 2000

Salary revision for the Home Affairs Uniformed Services (HUS) was made in Dec 1997. For 1998 and 1999, the Ministry monitored HUS salary competitiveness but found no need to make significant changes then, largely because the economy was still recovering from the economic crisis. In 2000, a comprehensive review was conducted covering officers in the Police, Singapore Civil Defence Force, Prisons and Central Narcotics Bureau. The aim of this review was to keep the HUS schemes in line with future labour market trends and to retain “choice employer” status. The study focused on the different elements that make up the total experience of a uniformed career in HUS including salary, benefits, career management, officer retention, continuous learning and development, and rank structures.

Outcomes of the study

Key pay related outcomes from the study were:

· Extension of retention payments to all HUS officers of Senior Station Inspector 2 equivalent rank and below. To reduce attrition of lower rank HUS officers, an existing scheme for prison staff was modified and extended to all HUS officers of Senior Station Inspector 2 equivalent rank and below in October 2001. Officers on the retention payments scheme receive the equivalent of one month’s salary each year during their first 6 years of service. Thereafter, the amount will increase to the equivalent of 1½ months’ salary each year from the 7th to the 10th year of service. Officers will be able to draw down these payments in the 6th, 8th, 10th and 12th year of service

· Pay adjustment. MHA adopted the principle that salaries should be pegged to market salaries (using age primarily as a basis of comparison) rather than against salaries in other public service schemes. As the study found that pay for officers up to Station Inspector and equivalent ranks lagged the market, with effect from 1 June 2001, HUS officers up to Station Inspector and equivalent ranks had their pay raised by one increment. Starting salaries for Corporals and Sergeants were also be raised by one increment from the same date. Senior Station Inspector equivalents and above, and other officers who have reached the maximum of their salary scale did not receive the adjustment as their salaries were found to already be in line with the market

· A new occupational superannuation scheme known as the INVEST plan was implemented in 2001. The aim of the fund is to help new officers (whose retirement age is lower than existing officers i.e. 50 for officers of Senior Station Inspector 2-equivalent rank and below and 55 for Senior Officers) transit out of service into their second career. Officers in this retirement fund scheme receive an additional contribution each month into their retirement accounts. The money in the retirement account is then invested. Serving officers were given the option to continue on their current terms or to opt for the new scheme (in which case they would also be agreeing to a lower retirement age and opting out of their existing pension scheme). An advantage of the new scheme is that, unlike the full forfeiture under the pension scheme, an officer on the INVEST plan may receive part of the accumulated benefits if (s)he retires before reaching the compulsory retirement age.

The Experience of Changing Pay Administration Arrangements

Experience of replacing fixed pay scales

In 2000 the Singapore Civil Service introduced a system of salary ranges to replace the existing system of salary points for its most senior staff ie Administrative Officers and political appointment holders. As a consequence, 14 Superscale and Staff Grades were banded and consolidated into 9 salary ranges, and the 4 timescale grades were each converted into salary ranges. This gave the Civil Service increased flexibility in personnel management and officers can be rewarded with merit increments within their salary range each year, depending on their assessed potential and demonstrated performance.

Salary Points |

Salary Ranges |

Political Appointments |

Staff Grade IV, V |

MR1 |

Deputy Prime Minister/ Minister MR1 |

Staff Grade III |

MR2 |

Minister MR2 |

Staff Grade II |

MR3 |

Minister MR3 |

Staff Grade I |

MR4 |

Minister MR4 |

Superscale B |

SR5 |

Senior Minister of State |

Superscale C |

SR6 |

Minister of State |

Superscale D |

SR7 |

Senior Parliamentary Secretary |

Superscale E |

SR8 |

Parliamentary Secretary |

Superscale G |

SR9 |

|

Senior Principal Assistant Secretary* |

R10 |

|

Principal Assistant Secretary |

R11 |

|

Assistant Secretary |

R12 |

|

Senior Administrative Assistant |

R13 |

|

Administrative Assistant |

R14 |

*: Newly introduced range.

Details of min and max for the above are not made public.

Staff on Superscale and Staff Grades were a better off as it meant that they no longer had to wait to be promoted in order to enjoy a salary increase. For the timescale Administrative Officers (ie those in the newly formed R10-R14 range), it meant that their increments would be at risk. However, as the working of the salary ranges was underpinned by the existing performance appraisal system, which was widely accepted and considered as being successful, this change does not appear to have resulted in any major unhappiness or discontent.

The key challenge in ensuring that the new system worked well was to educate supervisors on the importance of the appraisal process. In order to underscore the importance of the appraisal process, the ability to conduct and engage in performance appraisals is one of the pre-requisites for promotion to supervisory positions.

Experience of introducing performance-based rewards

As described previously, the Singapore Civil Service pay structure is distinctive in that it has performance related elements both in the monthly salary component (NPVP and MVC) and the annual salary component (the NPAA, AVC, SB and PB).

Performance bonus

The Civil Service Performance Bonus (which was first introduced to Superscale Officers and the Administrative Service in 1989 and later extended to all civil servants in 2000) allows the Civil Service to link pay directly with individual performance on the job. This gives the salary structure added flexibility and provides management a finer tool with which to reward deserving officers. The bonus amounts for all civil servants are set out below:

Officers |

Performance bonuses |

Majority of civil servants |

Base rate of 0.5 months of salary |

Administrative Officers in Superscale C and above |

Average 5 months of salary |

Administrative Officers up to Superscale D1 |

Average 3 to 4 months of salary |

Recent increase in variable component for senior civil servants and the GDP bonus

For the senior civil servants, the variable component of the 13th month - the NPAA, the AVC and the performance bonus together make up 30% of the total annual remuneration. In 2000, the proportion was increased to 40% for senior officers (i.e. Superscale G and above). This increase comprises individual performance bonuses and the GDP-related bonus (i.e. bonus which is linked to the state of the economy).

Economic growth in the calendar year |

Bonus months pay |

8% or more |

2 months |

5% (mid point of longer term growth potential of 4 to 6%) |

1 month |

2% or less |

0 month |

Source: Deputy Prime Minister BG (NS) Lee Hsien Loong, Civil Service NWC Award, Public Sector Salary Revisions and Review of Salary Benchmarks, Ministerial Statement on 29 June 2000

To incentivise and retain officers, the government also introduced a ‘bonus pool’ concept in 2000 but for senior civil servants only. Under this system, an officer would be paid half his/her performance bonus for the year immediately, and the other half will be placed into a bonus pool. The officer will be entitled to receive the amount in the bonus pool in two equal instalments 12 and 24 months later, provided (s)he continues in service. Officers who resign or are dismissed from the Service would not be allowed to withdraw any balance in the pool, although officers who retire are able to do so.

Performance management framework

Performance related pay is administered within the existing Civil Service performance management framework, which has been found to work well over the years (‘tried and tested’). The performance unit is defined primarily at an individual level except for the GDP related bonus that is dependent on the state of the economy.

There are two components in the Singapore Civil Service's performance assessment system: the reporting system and the ranking system (the so called Currently Estimated Potential ranking). The main assessment criteria for the reporting system are personal performance targets and trait-based criteria. The ranking system has two components: performance ranking and potential ranking (which is also considered in promotion and reward decisions). The main assessment criteria for the forced distribution performance ranking system is relative performance between teams or individuals.

On balance, the current performance management arrangements are considered to be quite successful, and they have worked well thus far as a foundation for supporting performance reward decisions. The existing structure ensures that performance/individual equity-conscientious civil servants are paid fairly and impartially according to market rates and are adequately rewarded for taking on progressively higher positions with increased responsibility, while those not willing to pull their weight will not be so favourably compensated. Some argue, however, that the existing arrangements tend to favour the ‘fair weather’ performers and those who “please the boss”. There is also a perception that loyalty is not always recognised.

Experience of simplification and decentralisation of pay administration

This issue has been covered in some detail above. In summary, however, two key changes have been made over recent years:

· Devolution of personnel management in the Civil Service to give ministries more autonomy in the appointment, confirmation and promotion of their officers. This was driven primarily by the desire to improve the responsiveness of personnel decision-making processes while not compromising on basic principles such as internal relativity and transparency.

The process of devolution was carried out in phases, and over the years more decisions have been decentralised from PSD to the various ministries. The outcomes have been greatly welcomed as promotion exercises can now be held every year, and vacancies filled with recruits chosen by the ministries themselves.

· Amalgamation of different schemes of service into broad Service Groups in the Civil Service. Employment and salary structures were streamlined and promotional grades were added where necessary to allow officers more promotion opportunities. This was aimed at enabling the Civil Service to better deploy and develop employees according to their potential and abilities rather than be constrained by the schemes of service that applied when they were recruited.

In introducing broad Service Groups, officers who moved from an incumbent salary-scale scheme to a new range-based scheme were given the option of joining the appropriate Service Group on no less favourable terms. Those who decided to remain with their current scheme of service would continue to be governed by the terms and conditions of their scheme. Whilst this has, to date, impacted only a relatively small percentage of civil servants (conversion to ranges is a gradual process), it has nonetheless been considered a success as more than 95% of those affected opted to join the Service Groups.

Some of the practical considerations in planning and implementation these changes are:

· Communicating the right message

· Bringing in the key stakeholders (both policy makers, the affected civil servants and those responsible for administering the change) and key people on the ground (such as the Union) early during the exercise and managing their expectations throughout.

Points of Interest

The key challenge in managing pay of civil servants in Singapore is to maintain the right a balance between paying enough to ‘attract, motivate and retain’ and aligning pay policies with the overall public service ethos (‘public above self’). In doing so, Government has had to take some hard decisions, including cutting pay. Whilst not popular, they were nonetheless implemented because Government chose to take a longer term view and a holistic perspective.

Whilst highly organised and systematic, the Civil Service pay structure and system is not considered rigid, rather it is fit for purpose and has demonstrated flexibility to meet external challenges. This is important in ensuring that there is a degree of transparency and consistency in the actual working of the structure, especially since the implementation of pay decisions has been devolved to the various ministries. Somewhat ironically though, information on the Civil Service pay structures is not readily available on the internet or in public documents (a practice common in the private sector). Although this has raised concerns about public accountability issues, the decision not to reveal too much information can be seen as being consistent with the Civil Service's view of itself as an employer competing in a small labour market.

Pay is a key component of the package to attract the best into the Civil Service but above and beyond that, it is recognised that as public servants, pay cannot be the sole factor. Over the years, therefore, great emphasis has been placed on training. Consequently the Civil Service has rather successfully created a perception of itself as a choice training ground for new recruits.

Pay administration for most grades of staff has been devolved to the various ministries. Although these are free to operate within pre-determined boundaries, the culture is such that there are unlikely to be any major deviations from set pay policies as ministries operate with the knowledge that they are part of the larger Civil Service. There have been instances of ministries wanting greater autonomy and the ability to pay higher salaries for their good staff, however, PSD's preferred stance on Civil Service salaries is for movements to fluctuate within a narrower band than is the case in the private sector. This is to allow for greater stability, which PSD believes is important for civil servants to be able to do their job well.

The Singapore Civil Service pay system is built on well thought out principles. One of the key challenges in the devolution of personnel functions, however, is to ensure that the human resource personnel and line managers in the ministries have a clear understanding of these principles and are able to apply them wisely, and not mechanistically. It has been stressed that even though the system is well designed, its successful implementation depends on the people who manage the system.

On balance, the Singapore pay arrangements work well in the closely managed, but pragmatic environment of Singapore. The current arrangements have evolved over a period of time and the implication of significant changes have been considered thoroughly before implementation. For example, it took close to five years of deliberation before a decision was finally made to implement the performance bonus for all civil servants. Also, the implementation of performance-related rewards was underpinned by an existing performance appraisal system that had credibility among staff and was considered to have worked well over the years. A pragmatic approach is also adopted in implementing pay related initiatives: systems are changed or designed for the future civil servants and implemented first for new recruits. Serving officers are then given a choice to opt into the new system. This approach has enabled Singapore to introduce quite significant changes without incurring major costs.

In implementing new initiatives, mid-level policy makers are cognizant of the importance of getting "buy-in" from the various stakeholders such as the HR employees of the various ministries, the Union, the civil servants themselves including the senior policy makers. For the latter in particular, it has been highlighted that part of challenge is in managing staff expectations to accept the fact that all the implications of any new policy or system cannot be foreseen and to be willing to change and innovate over time.

Key trends

Moving forward, the key trends include:

· Further strengthening the links between performance and pay

· Willingness to try out in a planned way, new approaches to remuneration that have been found to work in the private sector. At the same time, ensuring that these do not undermine the values underlying the Civil Service pay structures.

Pay ranges will be considered for Civil Service schemes in general, although their applicability to all levels of staff needs to be further evaluated.

End Note:

Background Reference Sources

i. "Yearbook of Statistics - Singapore 2001", Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade and Industry, Republic of Singapore; http://www.gov.sg

ii. "Public Service Reforms in Singapore", Janet Tay, http://magnet.undp.org/Docs/psreform/civil_service_reform; Personnel Policy Department, Public Service Division, Prime Minister's Office; "Yearbook of Statistics - Singapore 2001", Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade and Industry, Republic of Singapore; http://www.adminservice.gov.sg/main.htm; "The New Public Administration: Global Challenges Local Situation - The Singapore Experience", Paper presented at the biennial Commonwealth Association for Public Administration and Management (CAPAM) Conference, 21-24 April 1996; Principles of governance as outlined by Mr. Lim Siong Guan, Head of Civil Service, in the Singapore Country Paper for ASEAN Resource Centre, Seminar on Leadership, Ethics and Public Sector Reforms, 22 to 24 September 1999

iii. "Public Administration in Singapore: Continuity and Reform" by David Seth Jones, Handbook of Comparative Public Administration in the Asia -Pacific Basin, Ed. by Hoi-kwok Wong, New York: M Dekker, c1999

iv. "Economic Restructuring and Flexible Civil Service Pay in Singapore" by David CE Chew, Public Sector Pay and Adjustment - Lessons from five countries, Ed by Christopher Colclough, Routledge, Great Britain, 1997; "Wielding the Bureaucracy for Results: An Analysis of Singapore's Experience in Administrative Reform" by Jon. S.T. Quah, National University of Singapore, Asian Review of Public Administration, Vol. VIII, No.1 (July- December 1996)

v. Personnel Policy Department, Public Service Division, Prime Minister's Office; "Economic Restructuring and Flexible Civil Service Pay in Singapore" by David CE Chew, Public Sector Pay and Adjustment - Lessons from five countries, Ed by Christopher Colclough, Routledge, Great Britain, 1997; http://www.gov.sg

vi. Republic of Singapore "Competitive Salaries for Competent and Honest Government: Benchmarks for Ministers and Senior Public Officers", Singapore, White Paper, Command 13, 21st October 1994; Personnel Policy Department, Public Service Division, Prime Minister's Office

vii. Deputy Prime Minister BG (NS) Lee Hsien Loong, Civil Service NWC Award, Public Sector Salary Revisions and Review of Salary Benchmarks, Ministerial Statement on 29 June 2000; Deputy Prime Minister BG (NS) Lee Hsien Loong, Second off-budget measures 2001 - Tackling the Economic Downturn, delivered in Parliament on 12 Oct 01; Personnel Policy Department, Public Service Division, Prime Minister's Office.