Appendix C – New Zealand Country Summary

The Government Context Organisation of Government (see note i)The New Zealand Government is characterised by a parliamentary system and unitary structure. Members of Parliament are selected by mixed proportional representation. Parliament passes laws and acts in a scrutiny role, controlling taxation as well as public expenditure.

Executive authority is vested in the Prime Minister and all the Ministers, who form the Executive Council. A subset of those Ministers forms the Cabinet. Cabinet is the central decision-making body of the executive government. Its role is to determine and approve new legislation and policy proposals and priorities, and to co-ordinate portfolio responsibilities. Ministers must be Members of Parliament.

The Government is made up of:

· Three central Departments (i.e. the Treasury, the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, and the State Services Commission)

· 36 other Departments, which are usually policy making bodies but a minority have operational or coupled functions

· 160 Crown Entities, which are bodies created to be some distance from Ministers carrying out defined operational roles

· 19 State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and 10 Crown-owned companies. (These make up the commercial trading arm of Government.)

NZ has a widely devolved central (national) Government, but does not have a regional or state/federal structure. The local government sector is limited in powers.

Local government

There are two layers of local government: regional councils, and territorial (district or city) councils.

Regional councils are responsible for:

· Management of the effects of use of freshwater, coastal waters, air and land

· Biosecurity control of regional plant and animal pests

· River management, flood control and mitigation of erosion

· Regional land transport planning and contracting of passenger services

· Harbour navigation and safety, marine pollution and oil spills

· Regional civil defence preparedness.

Territorial councils (district and city councils) are responsible for:

· Community well-being and development

· Environmental health and safety (including building control, civil defence, and

environmental health matters)

· Infrastructure (roading and transport, sewerage, water/stormwater)

· Recreation and culture

· Resource management including land use planning and development control.

Civil Service overview (see note ii)

The Civil Service is called the Public Service. Staff employed in the wider public sector enjoy similar but not exactly parallel conditions and pay. In practice, their conditions are often more generous and their pay higher.

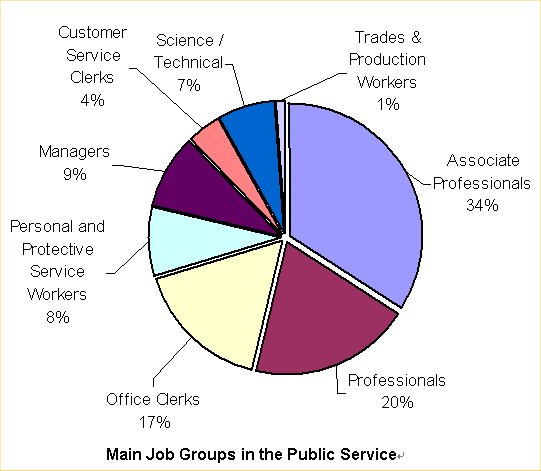

· The NZ public sector consists of 30,000 employed in government departments, 75,000 in Crown Entities and 25,000 in the trading sector.

· This represents 1.79% of the working population.

· In 2001, 7.4% of Public Service employees were on fixed-term contracts.

New Zealand has largely dispensed with Civil Service occupational categories and many equivalents to jobs in the Hong Kong civil service have been placed outside of the Public Service. For example:

· Chemists/Water chemists are in the Crown Research Units, which are Crown Companies with semi commercial objectives

· Engineers and surveyors were once in the NZ Public Works Department, which has been disbanded. Engineering and surveying is now a private sector activity

· This also applies to electrical, electronic and mechanical inspectors: only a small core remains in the Public Service. The Public Service has concentrated on setting services standards and monitoring their outsourced operation

· A number of agricultural and fishing officer functions are performed by the private sector, though a core does remain in the Public Service to set and monitor standards

· Environmental protection is in the hands of local government.

Of the equivalents to the Hong Kong Disciplined Services:

· The Immigration Service and Customs are part of the ‘core’ Public Service, and not separated even though they are uniformed and have some enforceable powers

· The Fire Service is a Crown Entity

· The Police Force is outside of either the Public Service or the Crown Entity sector, because they have constabulary independence. But they are very closely aligned to the Public Service in practice

· There is no Government Flying Service.

Values

The Public Service has an established mission of service to the Government of the day that is captured in various documents, principally the Code of Conduct. This has three overarching principles - public servants should:

· Fulfil their lawful obligations to the Government with professionalism and integrity.

· Perform their official duties honestly, faithfully and efficiently, respecting the rights of the public and their colleagues.

· Not bring the Public Service into disrepute through their private activities.

Public Sector Reform

Public sector reforms (see note iii)Reform drivers

The organisation, structure and functions of the Public Service has largely been shaped by the State Sector Act (1988), the Public Finance Act (1989) and the Employment Contracts Act (1991).

Factors contributing to a series of major public service reforms commencing 1984 include:

· The economic crisis and the conditions leading to it

· Frustration of ministers in the Labour Party cabinet with the weaknesses in the public service, which were about lack of clearly defined goals or management plan in most Departments; few effective control mechanisms for Departmental performance review; little management freedom in Departmental operations; too much emphasis on input controls; and no effective review mechanisms for dealing with poor performance by senior management

· A deliberate challenging of existing institutional arrangements by the Labour Government upon taking office in 1984. That Government had two terms of office until 1990. The challenge was continued, to a lesser degree, by the subsequent National Government.

Major reform initiatives

Since 1988 the NZ public sector has undergone continual reform both general and pay specific. Details are set out below.

· 1988: State Sector Act aimed to enhance efficient and effective public service management by increasing managerial autonomy and more clearly defining accountabilities; preserving the values of service to the community and integrity.

· 1989: Public Finance Act introduced a new legal framework covering the use of public resources.

· 1991: The Employment Contracts Act introduced a new regime for industrial relations and a new employment framework of contracts. There were also major reviews of State sector reforms to date, covering parliamentary accountability; the collective interest; strategy formulation by Cabinet; risk management; the relationship between ministers and Chief Executives; the role of central agencies; senior management development; and human resource and financial management.

· 1993: Significant restructuring of public service departments, with the creation of Crown Entities in the health, science, housing and transport sectors.

· 1994: Fiscal Responsibility Act introduced a requirement for the Government to publish and regularly update the fiscal state of the country, looking out over ten years.

· 2001: Strategic Business Plans as ownership documents for Departments, and Reform package for Crown Entities announced. The package is intended to make governance and accountability arrangements for Crown Entities clearer, more centralized and consistent.

· 2002: The Government has sponsored a major project called ‘Recreating the centre’ aimed at consolidating central agencies and their functions, and aligning the behaviour of Crown Entities with the core public service. It has been premised on the belief that NZ’s civil service had become too devolved and fragmented, and that a central core needed to take a more assertive and directive role.

Impact of the reforms(see note iv)

All initiatives have centred on the following themes and have had significant influence on the current operations:

· Decentralisation; resulting in greater managerial discretion of Departments and Crown Entities over inputs

· Commercialisation; leading to the development of a set of operating financial-based guidelines for the evaluation of Departmental cost-effectiveness and competitiveness

· Corporatisation; entailing the establishment of Crown companies and SOEs to focus on commercially oriented businesses

· Business-orientation, giving greater freedom on resources utilisation, greater clarity of objectives, and more streamlined structures – particularly in the Crown Entity sector

· Restructuring; leading to the substantial downsizing of the 'core' public service from 53 to 35 departments and agencies or about 86,000 to 34,000 full time equivalent staff between mid-1984 to end of 1993. But this was accompanied by a growth in the Crown Entity and trading sectors.

The period of time over which these reforms have been rolled-out means there is a higher likelihood that newer and younger staff are on individual agreements than the previous cohorts of public servants (the proportion of employees on individual agreements falls as age increases, from 72% of 15-19 year olds to 34% of 60-64 year olds). There is also a broad agreement that service to the public has improved in terms of efficiency, quality and responsiveness to customers, though there is thought still to be room for improvement in co-ordinating the agencies of the State to achieve a more seamless service to the public.

Pay specific reforms

Prior to 1988, the total State sector engaged in centralised pay negotiations, conducted between the State Services Commission (SSC), representing the Government as employer, and the Council of Trade Unions representing State sector unions. The negotiations settled on an annual general pay adjustment. Compulsory unionism, arbitration processes, and a relativities system were the pillars of the pay framework at this time. The State Sector Act of 1998 started a process of decentralisation.

Subsequent key pay specific reforms include:

· 1991: The Employment Contracts Act introduced greater flexibility in employment relations through enterprise based bargaining. The national system of employment arbitration in the case of employment disputes was also dismantled and replaced by individual contract law, with individual grievance procedures.

· 2000: Employment Relations Act repealed the Employment Contracts Act 1991 and introduced a number of changes to how employers, employees and unions conduct their relationships. The ultimate goal of the Act is to build productive employment relations, and for employers, employees and unions to make changes and work through issues themselves, by dealing with one another in good faith, with mutual trust and confidence. The new Employment Relations Act (ERA) 2000 also re-recognises the role of unions as important bargaining agents.

The Employment Contracts Act brought about significant changes in the Public Service. The Public Service Appeal Board, which heard all appeals against non-appointment from Public Service employees, was abolished. Departments now have their own appointment review procedures. The SSC also delegated all its powers for collective employment negotiations to Chief Executives of Departments and ministries. However, they are required to take account of the bargaining parameters set by Government and to consult the SSC about their bargaining strategies. (See “Legal framework” below)

Main drivers of this decentralised approach are considered to be devolution of management responsibility, locating decision making to the level at which it is best made (principle of subsidiarity), accountability, discipline, and transparency.

Impact of the pay reformsThe decentralised pay administration arrangements has brought about changes in the following areas:

· Flexibility in occupational classifications: Before the reforms, there was a standard set of occupational classes, with set pay scales and grades across the Public Service. Each department now has autonomy in determining job titles, occupational groupings and pay scales within budgetary constraints. There is a trend towards very broad, generic occupational groupings to suit agencies’ operational requirements and staff skill development needs. In the wider public sector – and in the workforce as a whole – the Employment Contracts Act brought about an increase in occupational flexibility, associated with a reduction in union membership and far less demarcation between unions.

· Flexibility in remuneration: As prescribed pay scales for occupational classes across the Public Service have disappeared, they have been replaced by a variety of remuneration systems. There is no longer a set appropriation dedicated to personnel expenditure. Each Department has responsibility for developing its own remuneration strategy in line with the strategic imperatives for the Department.

· Changes in contractual arrangements: Traditionally, many staff in the Public Service belonged to and were represented by their major union, the Public Service Association, which negotiated terms and conditions of employment on their behalf. Virtually all employees were party to Collective Employment Contract (CECs), which were called voluntary agreements or awards before the Employment Contacts Act. Employees can now choose who would represent them in employment matters, and provide for negotiation between employers and employees over whether contracts would be individual or collective.

· Labour supply and demand: There were concerns prior to the reforms that the rigid job classification system, and inflexible recruitment policy meant that the Public Service lacked the means to appoint and develop people with the skills necessary in a rapidly changing environment. The reforms changed the skill requirements for the Public Service and wider public sector, and also allowed much greater flexibility in meeting those changed requirements.

Overview of Current Pay Administration Arrangements

Pay administration principles and policies (see note v) Legal frameworkThe governing legislative framework for this decentralised market was the State Sector Act 1988 (SSA) and the Employment Contracts Act 1991 (ECA). The Employment Contracts Act (ECA) replaced compulsory unionism with voluntary unionism, removed arbitration and established enterprise bargaining in the place of national occupational awards. Unions were de-emphasised and, to an extent, replaced by the concept of bargaining agents (who could be any nominated person). These Acts facilitated the move towards “individualised work and performance contracts” as a replacement for the former “rule and process-based civil-service system” (Kettl, 1996, p.453).

The Employment Relations Act 2000 has rebalanced employment relations somewhat by requiring employers to bargain in good faith, recognising that bargaining power in settling new agreements is unequal, and advantages the employer. But it has not significantly altered the individualised and performance basis of employment of what are now called employment ‘agreements’ not contracts.

Key principles governing pay administrationThe pay policies of NZ are currently evolving to reflect the policies of the current Government, (elected in 1999), which have been formulated in reaction to over a decade of change.

In the decade between 1988 and 1999, pay policies were dominated by two principles: decentralisation, and a belief in the efficacy of comparatively unregulated market forces to set pay levels. The approach up to 1999 has been market driven, subject to the ability to pay. The main control has been fiscal affordability, rather than a set of employment rules. The pay regime was performance based. There was a significant element of pay that was “at risk”, especially for managers and senior professionals.

The State Services Commission has prescribed general policy parameters under which Departments and Agencies are allowed to negotiate the terms and conditions of employment with their employees. These include:

· ‘Good employer’ and equal employment opportunities provisions

· Requirements relating to notifying vacancies, making appointments on merit, and implementing appointment review procedures

· Developing a Senior Executive Service (in conjunction with the State Services Commission)

· Good practice guidelines for bargaining strategies.

Pay structure and componentsGrading and base pay structures

There is no centralised pay structure with grades spread across all Departments and ministries in the Public Service. In its place exist broad occupation ‘families’ with internal salary ranges. For example, the occupational family of policy analysts falls into three bands: analysts, senior policy analysts and managers (some Departments also have a special category for a select few who have management level skills but do not want to be managers). This system provided the most flexibility, aligned with fiscal control and performance incentives. The one exception is the centrally controlled pay policies and structures for Public Service Chief Executives.

Chief ExecutivesFrom 1988 the SSC used job evaluation to evaluate Chief Executive (CE) roles. Until 1997, CE’s pay structure was based on a payline, the potential remuneration rising according to the size of the position as measured in job evaluation points. From time to time the Government agreed to shift the entire payline or to allow more tolerance around the line but the SSC found remuneration issues were often less in the macro policy than in setting pay for specific positions requiring skills that were scarce in the market. The payline also limited the capacity of the SSC to recognise consistently high performance by a specific individual.

A new pay structure, settled in 1997, was built on a series of bands (currently 5 bands). Each band covers larger job sizes as measured in job evaluation points. The SSC still operates inside the total sum of money made available each year by the Government for CE pay, and the PM and Minister of State Services must agree to the results of the Commissioner’s negotiations.

Under the previous policy, the CE’s packages were composed of separate elements: a base salary and a set of benefits in kind (motor vehicle, employer superannuation contribution, professional fees and an expenses allowance of $1000 pa). Since 1997 the pay is calculated according to a total remuneration approach, as a single sum. CEs can then choose the combination of pay and benefits they wish to receive. Whatever choices, there are no extra costs imposed on the employer.

Performance is linked to remuneration by an increase in incentive pay from 10% (before 1997) to 15%. This is calculated on the total package rather than base salary, as before 1997. The performance pay is against the targets set out in a strategic incentive plan (SIP), built around the policy priorities of the Government. Measured against the fixed proportion of CE’s packages (salary and benefits in kind, but excluding performance incentives) the average increase in Public Service CE remuneration was 7-8% in 1996/97 to 1997/98 (when the changes were made). The proportion of CE pay that is comprised of performance incentives rose from 4.3% to 6.9% of total remuneration in the same period. Along with fiscal constraints, CE pay is one centralised feature of pay policies and structures and it sets an influential precedent in the Public Service and wider State sector.

DepartmentsEach department designs and manages its own pay structure. Departments have taken different approaches to pay ranges but there was a common pattern of using external job sizing approaches to revalue jobs into larger families, and to have steps between the minimum and maximum points. Staff were generally hired within that range so that performance incentives existed, even for very experienced staff.

Many Departments and ministries initially sought external help from consultants and advisors. But they aimed to build up internal resources rather than permanently outsource what was considered a core organisational function. Staff and unions are involved in the design of the system which includes job sizing, job descriptions, ranges of rates and performance reviews, but the systems and final decisions on performance and pay are managed by the senior managers of the department.

Pay systemDivision of roles and responsibilities for pay administration

NZ, unlike other countries, devolved responsibility for HR management to the Department level without first setting in place Government-wide policy frameworks or guidelines beyond those in the State Sector Act. Apart from limited restraints in the area of industrial relations, Departments were free to develop their own strategies, policies and practices. However this was modified over time and a defined set of bargaining parameters grew in size and specificity.

In NZ’s devolved model of government, the Treasury has been highly influential in setting the overall fiscal parameters. The annual budget process sets the degree of fiscal movement a Department could expect. This movement was not exclusively a pay movement but a total package for the Department, including the funding of new policy and operations. The SSC co-coordinated bargaining parameters and in addition, controlled CE pay policies and structures. Since 1999, the Government has revitalised the role of the Commission as a central co-ordination body, with a responsibility to bring the devolved system together around a new set of bargaining parameters. These parameters now place more attention on the development and maintenance of capability in the Public Service.

Departments are able to develop policies for their internal implementation, with the maximum amount of flexibility to suit their business, within the centrally determined fiscal conditions. They decide on pay within that total package, subject to the bargaining parameters set by the Government.

There are moves since the Employment Relations Act 2000 to reintroduce unions back into the pay making process, though their long absence and consequent declining membership has left them severely under-equipped to fill their revised role.

Departments: movement within pay bands

There are no automatic increments. Movement within a range is based on performance appraisal, and movement to another band (e.g. analyst to senior analyst) is normally by formal appraisal by a panel set up within the department.

Pay levels and movement are constrained by overall budgetary considerations applying to the Government as a whole, and then cascaded down to each Department. There is no longer a set appropriation dedicated to personnel expenditure.

The market determines entry pay, although education may be one factor. Pay rates for entry-level jobs in the public sector are similar to those in the private sector although the gap widens as job size increases. Public sector senior management positions (including Chief Executives) tend to be paid about 80 –85% of the pay rates for equivalent positions in the private sector. The gap is slightly larger when incentive payments are included.

System and mechanism for determining pay level and pay adjustments (see note vi) For the Chief Executives pay, the SSC makes comparison to CEs working in the wider State sector, rather than to the private sector. For their staff, Departments generally compare across other Departments and ministries on remuneration, either through active co-operation or through the effects of market forces, which have required Departments to understand what others pay.As an example, the Department of Labour (DoL) used to employ a payline approach to revalue jobs. Job sizing was used to group roles into job families, in a band with an upper and lower limit. The job sizing was carried out for each job family within each of the six service units in the Department, with an allowable variation of 5%. Each year the payline was updated with market data from a variety of sources. If a divergence showed that this exceeded + or- 5% of the previous payline, then an adjustment was made to pay to bring it in to line. However, because the payline approach was seen as over smoothing changes in the market, DoL has now adopted a “basket” approach. Two broad types of surveys are conducted:

· Position-based job survey approaches, where DoL job descriptions are compared with generic job descriptions in the same category (e.g. DoL safety inspectors with inspectors generally)

· Job-evaluation approaches, where a job is evaluated from scratch without comparison.

DoL recognises it has a special problem when the Public Service is the only employer of specific roles e.g. Immigration Officers. As such, while the Public Service is used as the basis of the comparison for many positions, for these and most senior positions the whole job market in public and private sectors is used. DoL aims to compare at the median point, accepting it is not a market leader, but it is under some pressure with some of its service units (particularly its policy unit) to raise the comparison level.

Although the basket approach answers the problem identified with the payline approach, there are still internal variations between the service units (up to NZ$15,000) that are causing concern. There is also concern about the accuracy of the position evaluation methodology (used in both payline and the “basket” approach), as persuasive position holders can sway the objectivity of the exercise.

Arrangements for the Disciplined Services (see note vii)

The Disciplined Services in NZ also operate under devolved and decentralised management. Customs and Immigration are both departments in the core Public Service, and their conditions of services and pay are largely in line with the remainder of the Public Service. Police stand outside the Public Service because of the independence the Police need from the political process. The Police Commissioner is appointed directly by Parliament, but the last appointment was facilitated by the SSC – indicating the extent to which the Police are inside the Public Service by convention, if not by law. Legislation is now in train to confirm this approach to the Commissioner’s appointment.

One feature common to all the above services is that they remained strongly unionised in comparison to the ‘civilian’ Public Service, even in the decade of radical change in NZ. While changes in pay policies and structures extended to both civilian and Disciplined Services, it was widely recognised that the changes were more difficult to implement in the disciplined forces. There have been several contributing factors: strong unions, older workforce profiles, and a greater reluctance to identify and measure performance because of the culture of strong hierarchies and ranks achieved through years of experience.

Police ServiceThe NZ Police are distinguished from the Public Service by having no right to strike, and by having an compulsory arbitration procedure with ‘final offer’ arbitration at the end of it if negotiations fail. Final offer means that each party has to state its position and what it wants, and the arbitrator chooses one of the offers. There is no right of appeal.

While final offer arbitration is intended to modify extreme outcomes, it has worked against substantial change and has led to conservative outcomes over time. Typically, when a range of complex issues go to the final offer, they are simplified to win the contest. This has meant matters of pay details have been avoided in favour of a percentage blanket settlement.

The efforts to improve the relationships and environment led to a ‘Police Negotiating Framework’ in 1995, based on good faith- and information-based bargaining. Arbitration was required in 1997/98, but the last two bargaining cycles since then have been settled in negotiations without the need for arbitration.

The Police began a process of job sizing following the introduction of that framework, and constructed a payline, job families and ranges of rates with performance-based progression. Performance-based pay has not been successful however, and acts in a fashion similar to increments. The job families are generally linked to ranks, but not absolutely. Historically, rank was not always given because of job size (an example has been the ranks of those in the Police Training College).

The Police Department is divided into sworn and non-sworn employees, which was felt to be widely divisive. Prior to the Police Amendment Act 1989, the State Services Commissioner was the employer of non-sworn employees, and sworn employees were under the Police Commissioner. The Act brought them together, but did not obliterate the history. Though there are two different frameworks for pay, there has been greater success in joining the remuneration setting processes into one industrial negotiation. However, links are made to the wider job market for non-sworn employees, but not for sworn officers.

Fire ServiceThe employer of fire service personnel is the Fire Service Commission, which reports to the Minister of Internal Affairs. For pay and conditions of service, the Fire Service is divided into two, with two associated paylines: the ‘base’ of 1690 Firefighters, and the 434 management and support staff.

Pay and conditions for the ‘base’ fire-fighters are established through a fixed point salary, which is skills-based and established by a collective employment contract negotiated with the Fire Service Association (union). There are defined hierarchies. Employees start as Firefighters, and after two years normally progress to be Qualified Firefighters. After five years progress can be made to Senior Firefighterstatus. This is an automatic progression as long as time is served and skill levels are attained through courses and examinations. Then there are two levels of officers: Station Officer (who is the first line supervisor for a crew of 4 Firefighters of various ranks); and Senior Station Officer.

For historical reasons, there have been only modest attempts to radically reform these arrangements for the ‘base’ fire-fighters. A long history of difficult pay negotiations and a strong union meant that change has not been possible at this level. Performance pay and bonuses have not been used among these employees.

Change however, has been made to the management in the Fire Service. The change was implemented largely through an organisational restructuring of the Service, which required senior staff to reapply for jobs. Job sizing was carried out for all non-operational and management jobs. Non-operational staff have been indexed against the public and private sector job market (all jobs) because the Service recruits from that whole market.

Non-operational staff are paid in relation to performance – both in base salary movements and by bonuses. The performance appraisal is not directly tied to pay reviews but it does inform the process. Performance is linked to objectives and targets.

Customs Service

Unlike the Fire Service, the NZ Customs Service has not attempted radical restructuring but has sought to introduce change incrementally. Resistance to change has been high and industrial relations have been divisive. Older staff have remained on dated conditions and, for instance, impose a very high cost in overtime (13% of staff have between 30-40 years of service, and 25% between 20-30 years).

The history of industrial relations has led Customs to adopt short-term expedient actions in attempting to introduce changes in conditions and pay, such as atomising pay scales around narrow, specialist job descriptions rather than broader job families. This is contrary to the trend in the rest of the Public Service. The Department was also slow to introduce performance management and performance related pay.

A crisis point was reached in 1998, with a financial deficit partly generated by an expensive new IT system. The Department was forced to restructure to drive down costs, moving to a national service from its original regional basis. A competency framework was put in place. This allows on-job skills training and recognition, with pay consequences.

The Experience of Changing Pay Administration Arrangements

Experience of replacing fixed pay scalesThe NZ Public Service replaced fixed pay scales with pay ranges following the State Sector Act 1988. Most departments started with the traditional fixed scales and progressively re-sized jobs into job families with ranges within them, largely determined by performance. (See details of the arrangement in “Departments: Movement within pay bands” in the previous section)

The aim was to achieve greater flexibility in order to engender improved performance and greater financial discipline. There was also a strong belief in the superiority of the market over centralised intervention in determining pay.

Coverage extended to both civilian and disciplined services – but was more difficult to implement in the disciplined forces. This had several contributing factors: strong unions, older workforce profiles, greater reluctance to identify and measure performance because of the culture of strong hierarchies and ranks achieved through years of experience.

Fiscal discipline was maintained by the wide use of ‘one-off’ performance bonuses rather than rises in base pay. However, the current Government, whilst not wanting to wind back an emphasis on performance, has made it clear that in future it wants good performance to be rewarded through consolidation into the base pay of employees.

Experience of introducing performance-based rewardsThe NZ Public Service introduced performance appraisal systems, leading to performance pay, in the late 1980s. The responsibility for this was at the Department level.

New Zealand embraced performance appraisal and performance pay to drive and lift performance in the Public Service. This related to a widely held view by ministers in the Government that the Public Service was under-performing. At the same time, the influence of the private sector was very large and it was recognised that rewards and sanctions needed to go together. The aim was to create an internal labour market in the public sector to exert pressure on performance.

Performance management framework

Performance appraisal systems and performance pay is largely at the individual level, though a number of departments also reward teams where a team project has been successful.

It operates on a hierarchical basis: CEs have a specific performance agreement with the State Service Commissioner who is the apolitical agent of the minister(s) that the CE serves. This performance agreement is based on targets to be achieved, and standards of agreed behaviour that are then cascaded down from the CE to the senior management of the Department or ministry. The managers in turn expect achievement of certain targets and demonstrated behaviours from their staff. A range of approaches is encouraged, as long as the approach is valid. The Balanced Scorecard is one of the approaches adopted.

Performance based rewards follow from the performance appraisal system.The appraisal systems operated vary between Departments but invariably involve a blend of peer judgements and objective data on a range of criteria, including qualitative and quantitative skills, communications and interpersonal skills, and evidence of outputs. Competency frameworks are very common as a guide to assessment – usually adapted to the specific work of the Department.

Budgeting for pay movement

Departments take the responsibility for budgeting for performance-related pay. The CE has full power to make independent decisions but there are conventions that are observed, and the State Service Commissioner and the Head of the Treasury will ask questions if the size of the pot appears excessive. However, a newly formed organisation, or one that has aging staff, or has new tasks requiring new capabilities, will be expected to have active strategies to find or reward the necessary capabilities.

Typically, the HR unit within the Department has the role of determining the amount that is put into reserve for performance-related pay. They normally keep extensive records of previous years decisions, and have the records and profiles of staff at hand in order to make their recommendation.

Forms of performance payThe majority of public servants have a performance related element to their pay. The scale, however, varies with the position, and with the policies of the department involved. There has been some scaling back from the 1990s when a substantial element of senior managers and professionals pay was “at risk”. For other staff too there has been a reduction, for example the Department of Labour has decreased its performance related pay element from 5% to 2.5% in 2000.

Performance-related pay comes in a range of forms:

· Bonuses, typically paid at the completion of a defined project (that is, the bonuses can occur throughout the year, on a continuous basis). The use of one-off bonuses is declining however, under the present Government’s policies

· An advance in the band of salary that the staff member is in. This embeds the performance pay into the ongoing salary of the recipient. This advance in base pay is typically only made once a year at the formal annual appraisal, but departments usually have policies that allow a manager to make such a recommendation at any time of the year, particularly if performance is outstanding or the likely recipient needs recognition to retain their services

· An advance in the salary band to a higher band, as in fewer cases. This decision is usually on the basis of sustained performance, and again, except in exceptional circumstances, it is the subject of a review panel, not the decision of the manager of the unit in which the recipient works.

The Police noted that their performance management system did not work as intended: some units within the Police set aside sums of money that were then split evenly between those who were eligible – in effect working like annual increments.

Impact and success of change

Performance appraisal and rewards are now firmly embedded in the culture of the NZ Public Service and, with few exceptions among professional level staff, is positively embraced. The financial implications of the reforms in the 80s and 90s were considered positive by the Governments of the day. Labour costs were held and labour productivity in the Public Service improved.

From the point of view of Public Service managers, the performance appraisal and rewards system is a way of learning from feedback, with the opportunity to lift performance and grow in the role.

It is accepted less by staff in lower positions, because they perceive that the rewards go the prominent positions. In many departments this is recognised and addressed by ensuring sums of money are dedicated to lower positions, and the same system of performance targets and objectives is used to moderate that negative perception.

Issues arising and future developmentsThe new Government has moved to ‘mainstream’ performance pay into the base salaries of staff. One implication is that it is becoming locked into future pay, and management may be more cautious in using it. However, performance and base pay have been strongly linked in NZ since 1988 and the new Government is not overturning that.

Experience of simplification and decentralisation of pay administrationThe State Sector Act (1988) and the Employment Contracts Act (1991) significantly altered the pay administration of the NZ Public Service. Essentially, central structures and mechanisms for pay were taken down and the responsibility passed to the CEs of the Public Service organisations.

Before the State Sector Act of 1998, the State Services Commission was the central personnel authority for all Departments in Public Service. It employed all Departmental staff, and prescribed personnel policies and procedures in the Public Service manual. The State Sector Act devolved responsibility for human resource management from the SSC to the Chief Executives of Departments, within parameters defined in the Act.

Approach to introducing these changes

The implementation was given some direction by the central agencies, and the State Services Commission in particular. But the SSC delegated all its powers for collective employment negotiations to CEs of Departments and ministries, and implementation was largely devolved. However, Departments and ministries were required to take account of the bargaining parameters set by Government and to consult the SSC about their bargaining strategies.

Many Departments and ministries sought external help from consultants and advisors. There was a concerted move, however, to develop and maintain internal resources rather than permanently outsource what was considered a core organisational function.

Impact and success of the change

From the point of view of Public Service managers the changes were a success, because they had more direct control over a key item of resource capability and expenditure.

From the point of view of some employees the changes shifted power markedly from organised labour (unions and professional bodies) to the employer. The balance has come towards the centre with the repeal of the Employment Contracts Act.

Issues arising and future developmentsNew Zealand continues to maintain a highly decentralised pay system but the new Government is seeking to recreate a centre to tie that decentralised system into a more cohesive whole. This translates into tighter central bargaining parameters. The fiscal control that has always dominated in NZ continues, but the Government is willing to make more investment in departments showing signs of strain. An example of this is the Department of Courts, which received a large sum for staff recruitment and development outside of the 2001 Budget cycle.

Points of Interest

Key factors which have shaped and facilitated current pay administration arrangements

A number of key factors underpin the success of the current pay arrangements in New Zealand:

· The reforms in pay policies and structures were part of much larger reforms to the role and business of Government. The importance of this cannot be overestimated. Fiscal disciplines for departments and a strong accountability system preceded the HR reforms and provided the necessary parameters for the market approach to pay policies and structures

· NZ believed that the differences between agencies in the Civil Services outweighed their similarities, and was prepared to have different job structures with internal ranges of rates to suit the profile of the agency, and its culture and its business. This did not mean abandoning a ‘Civil Service’ bound by common values, but it required those values to be revisited and found, not in common structures and pay, but in common constitutional roles and a common focus on serving the public

· There was a wide acceptance that ranges of rates and related performance management were not going to be perfectly achieved first time, and that all parties needed to work through the resolution of issues and implementation. Clear processes and staff involvement were crucial along with a firm management commitment to implementing ranges of rates. In particular, management was required to model the disciplines that staff were asked to follow

· Maintaining fiscal discipline while achieving performance was NZ’s primary concern. One feature of its maintenance was the wide use of “one-off’ performance bonuses rather than rises in base pay. The whole pay system was inside the management control of the Departments, which had strong incentives to cap the pay movements of their staff. But longer term, the effect of the downward pressure on departments to manage their costs has meant that Departments have ‘done more for the same’, or only slowly growing, funding over a decade. This has led to some crises in capability, which now concerns the current Government

· Another factor contributing to the current arrangements is the Government’s recognition that pay reform is an evolving issue and there has to be an acknowledgement and willingness to change tack when something has been proved not to work – whether it has been disadvantageous to specific groups or to the “business” of Government as a whole.

Key trends

Against the background of these highly decentralised pay administration arrangements, we note the following key trends in the New Zealand Public Service model:

· While there is a strong emphasis on performance and linking performance to pay, the current Government has moved to give more emphasis to ‘mainstream’ performance pay built into the base salary, rather than one-off performance bonuses

· To maintain a highly decentralised Public Service pay system, the Government is seeking to enhance the central co-ordination of pay administration in order to create a more cohesive whole, effectively through two measures: tighter central bargaining parameters and more flexibility from the centre. The centre can on one hand exercise stringent fiscal control to guard against excess resources and, on the other, make more investment in Departments showing strain

· Many Departments and agencies have commissioned external consultants and advisors in developing and implementing their own pay arrangements to meet their own requirements. Seeing this as a core organisational capability, they tend to seek help to build up internal resources and skills rather than permanently outsource.

End Note:

Background Reference Sources

i. www.stats.gov.nz; www.oecd.org; “Towards Better Governance: Public Service Reform in New Zealand (1984-94) and its Relevance to Canada”, Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 1995; and advice from the State Services Commission

ii. State Services Commission HRC Survey 2001; and State Services Commission: Code of Conduct 1995 and 2001

iii. www.oecd.org; “Towards Better Governance: Public Service Reform in New Zealand (1984-94) and its Relevance to Canada”, Office of the Auditor General of Canada, 1995

iv. An independent study of the reforms by Prof Alan Schick from Maryland University; State Services Commission HRC Survey 2001

v. “Bargaining Parameters and Guidelines, Including Guidelines on Use of One-off Performance Payments and Other Special Payments, Approved by Government” from SSC; comment from the PSA, the main Public Service union, the partner in the “Partnership for Quality” agreement with the SSC, which represents the Government; and interviews with senior DoL personnel in the Office of the Chief Executive

vi. Pay Movement Trends and Labour Cost Index, Statistics New Zealand; and interviews with senior DoL personnel in the Office of the Chief Executive

vii. Interviews with the Director of HR in the NZ Fire Service.